In the Citi GPS Disruptive Innovation series, we have highlighted amazing new advancements in healthcare over the years — from immunotherapy, and CRISPR-based gene editing to virtual care and blood tests for cancer. One healthcare area notably absent from the innovation series is antibiotics. In the U.S., 251.1 million antibiotic prescriptions were written in 2019, making it the second most prescribed drug category behind cholesterol reducers. But half of the antibiotics commonly used today were discovered in the 1950s, and the last antibiotic class successfully introduced as treatment was discovered in 1987.

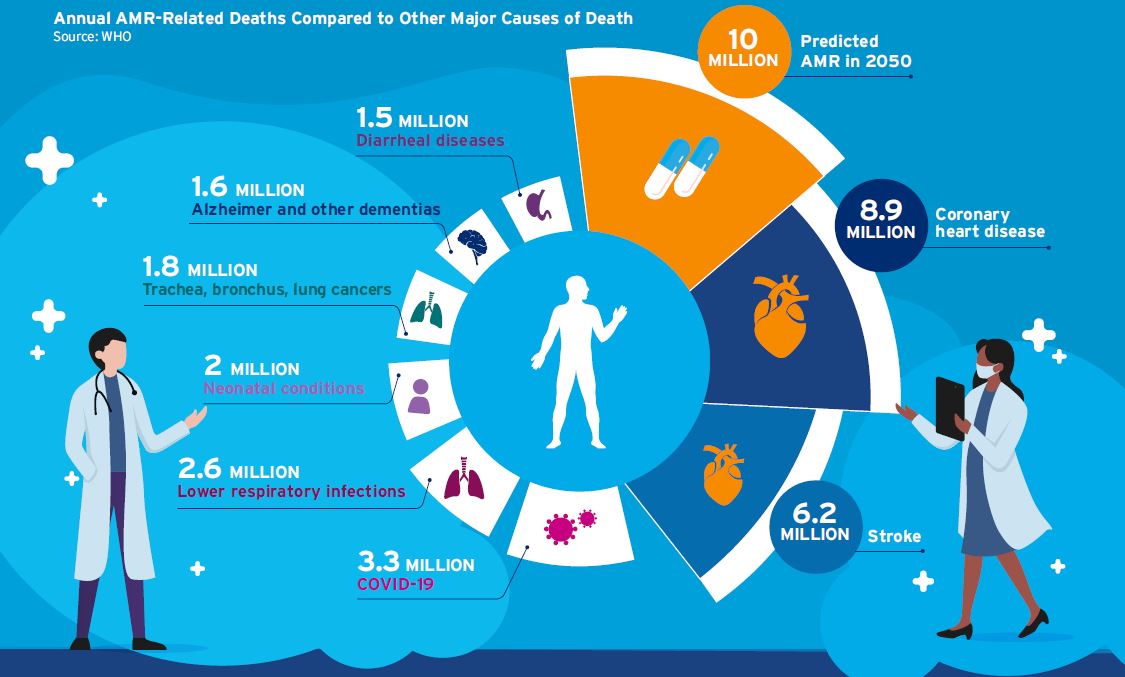

Why is this an issue? Because bacteria are increasingly becoming resistant to today’s antibiotics. In 2019, 4.95 million deaths were associated with bacterial drug resistance, with 1.27 million deaths directly attributed to it. If the issue of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is not addressed, it could lead to 10 million deaths by 2050.

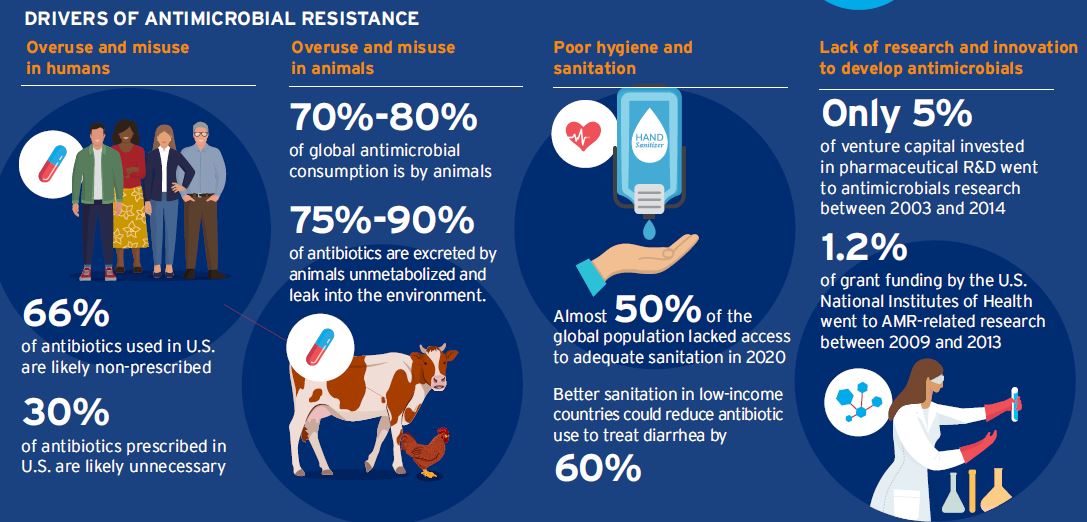

The drivers of AMR include overuse and misuse of antibiotics in humans and animals, poor hygiene and sanitation, and a lack of research and innovation to develop novel antimicrobials. At the same time, climate change is exacerbating many health challenges. Rising temperatures have increased the frequency and intensity of outbreaks of some diseases, as well as their geographical scope. Extreme weather can also increase the burden of infectious disease. Flooding leads to increased agricultural run-off as well as sewage contamination, which both increase the risk of disease spread. And as extreme weather increases, populations become displaced as homes become uninhabitable and access to potable water is threatened.

The report that follows looks at interventions that could avert the worst outcomes, and although AMR is a significant problem, many solutions are within reach. However, these solutions require the collaboration of a broad range of stakeholders, including the public and private sectors as well as civil society.

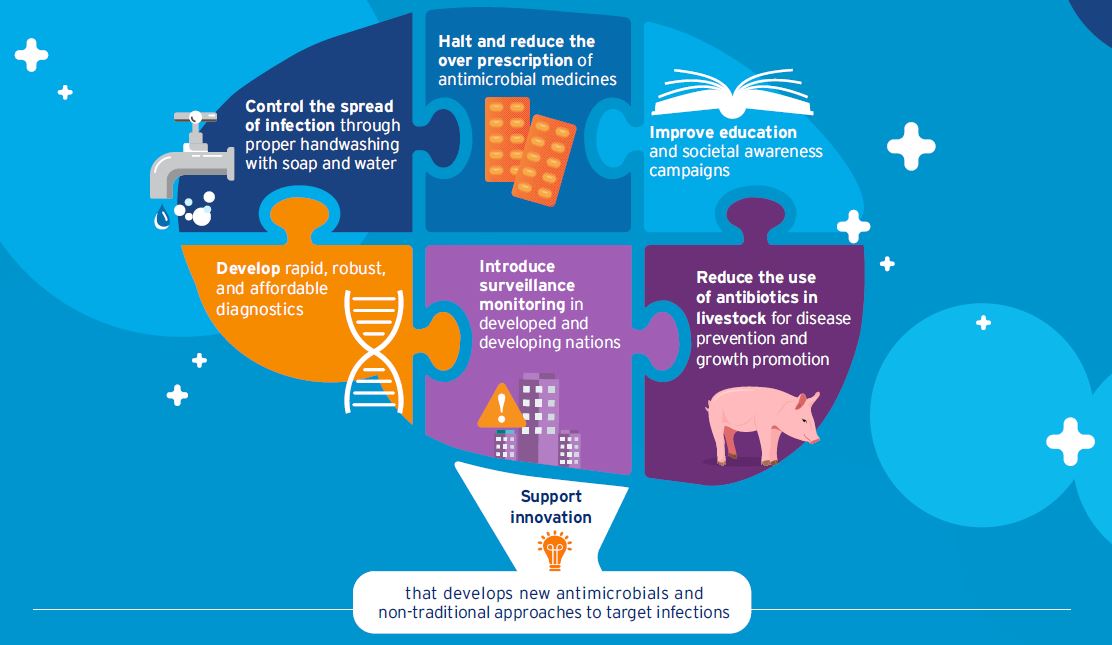

The first step in addressing AMR is reducing the burden of infectious disease. This can be done through improving sanitation and developing vaccines to prevent infections in both humans and animals. The second is reducing the use of antimicrobials in humans and animals by raising awareness on AMR, reducing unnecessary antimicrobials in food production, and developing rapid diagnostics. Facilitating innovation with investment in early-stage research and drug discovery will help in the quest for new novel antimicrobials. Finally, implementing steps to curtail the spread of resistance, such as strengthening global surveillance of drug resistance and improving treatment of wastewater with attention to antimicrobials.

Most importantly, the report calls for tackling AMR with the same effort as climate change. We view AMR, climate change, and biodiversity loss as closely related; this aligns with a “One Health” approach, which recognizes that animal, human, and environmental health should be considered holistically.

Based on discussions with experts throughout the report, policymaking appears to be the single most effective starting point in tackling AMR. The report summarizes their views and provides key recommendations for policymakers.

If we fail to protect the current suite of antibiotics and invest in research and development into new antibiotics, we could find ourselves in a scenario where most, if not all, antibiotics no longer work. This would limit our ability to treat common infections. In 2019, an estimated 1.27 million deaths globally were directly attributed to AMR and by 2050 up to 10 million may die from AMR-related illnesses.

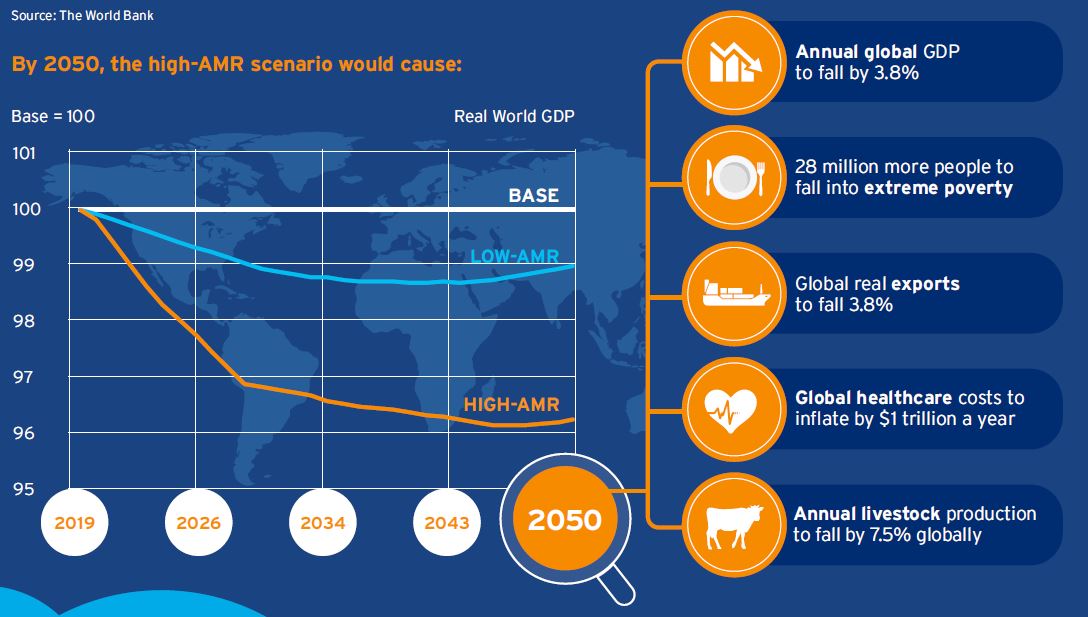

Using two scenarios corresponding to low and high AMR impacts, World Bank simulations have quantified the potential economic losses from AMR globally between 2017 and 2050.